Craniotomy

Craniotomy (Latin: cranium= the skull, esp. the part enclosing the brain; –otomy=cutting) involves the surgical removal of a part of the bone from the skull (called bone flap) in order to access the brain for surgery. The location of the bone flap removal depends on the size and location of the lesion and on the presence of brain structures that may be in the way. At the end of the craniotomy, the bone flap will be put back in place with tiny plates and screws. However, in some cases (e.g. due to swelling of the brain), the bone flap will be permanently removed – this is then called a craniectomy (-ectomy=surgical removal)

Craniotomy (Latin: cranium= the skull, esp. the part enclosing the brain; –otomy=cutting) involves the surgical removal of a part of the bone from the skull (called bone flap) in order to access the brain for surgery. The location of the bone flap removal depends on the size and location of the lesion and on the presence of brain structures that may be in the way. At the end of the craniotomy, the bone flap will be put back in place with tiny plates and screws. However, in some cases (e.g. due to swelling of the brain), the bone flap will be permanently removed – this is then called a craniectomy (-ectomy=surgical removal)

Indications for a craniotomy

A craniotomy may be performed for various reasons. Conditions such as brain tumors, blood clots, aneurysms (abnormal “ballooning of the artery due to weakness of the arterial wall) or an abnormal collection of blood vessels in the brain, called Arterio-Venous Malformation (AVM) are the most common reasons for a craniotomy. Other indications for a craniotomy can be the surgical treatment of neurological diseases (e.g. epilepsy or Parkinson’s disease) or the implantation of a medical device into the brain (e.g. to help monitor or regulate the pressure in the skull). Lastly, injuries such as skull fractures, a tear in the membrane lining the brain, or foreign objects in the brain can warrant a craniotomy.

Small, coin-sized craniotomies are called burr holes or keyhole craniotomies. These craniotomies are often used as minimally invasive procedure. The burr hole craniotomy is often sufficient for procedures, such as the insertion of a medical device such as a shunt into the ventricles to allow for proper draining of the cerebrospinal fluid, to take a biopsy of brain tissue or to drain an abscess or hematoma and hence reduce pressure on the brain.

Large or complex craniotomies are typically necessary for the treatment of larger tumors, aneurysms, AVM’s and skull fractures or injuries. These craniotomies often fall under skull base surgery because they often involve the removal of a portion of the skull that supports the bottom of the brain (the skull base). The skull base is where delicate cranial nerves, arteries, and veins exit the skull.

Computerized imagery and guidance

Neurosurgeons often use sophisticated computers to plan these craniotomies to help locate the lesion and the sensitive structures around. Guidance of computer imaging can also be used during the craniotomy (called intraoperative monitoring). Different systems, with and without localizing frames, can be used for this type of monitoring during the craniotomy, which is then called stereotactic craniotomy. Scans made of the brain, in combination with these computers and localizing frames, provide a three-dimensional image, for example, of a tumor within the brain. This imagery is very helpful in reaching the exact location of the lesion. Furthermore, endoscopes can also be used to precisely monitor and direct the instruments that are used during surgery.

The surgery

The surgery is usually done under full anesthesia, but under specific circumstances, sometimes the patient will be awake and only local anesthesia will be used. Surgery can take as little as 3 hours, or as long as 10+ hours, depending on the circumstances. The surgery consists of a series of steps.

- First, a skin incision is being made through the scalp (usually behind the hairline).

- The skin and muscle are folded back and kept in place with surgical clips, to expose the skull.

- Then, one or more small holes (burr holes) are being drilled through the skull. A surgical saw is being inserted through a burr hole to cut out the bone flap. The bone flap is being removed and stored until it can be replaced at the end of the surgery.

- The membrane around the brain is being cut open and folded back to expose the brain.

- The neurosurgeon uses a surgical microscope to visually enlarge the tiny structures in and around the brain. Neurosurgeons use a variety of very small tools and instruments to work deep inside the brain, as well as computer-imagery guidance to help them locate the problem and the sensitive structures around it.

- Once the problem is resolved, the neurosurgeon closes the membrane around the brain with sutures, and puts the bone flap back in place. Tiny plates and screws will hold the bone flap in place. A temporary drain may be installed to help remove blood and fluids and enhance the healing process. Finally, the muscle and skin is folded back and stitched together, before a big dressing will be places over the incision.

After surgery, patients typically remain hospitalized for 4-7 days, and after that recover at home for about 2 months. During this time, most activities will be restricted, including lifting, bending and driving. Yet, there are great variations in the recovery times and our surgeons will discuss specific expectations for your surgery, and will closely monitor your recovery process.

Why UPMC?

Tri-State Neurosurgical Associates-UPMC

Administrative Oakland Office Address:

Presbyterian University Hospital

Department of Neurosurgery

Suite 5C

200 Lothrop Street

Pittsburgh, PA 15213

Phone: 1-888-234-4357

© 2013 Tri-State Neurosurgical Associates – UPMC

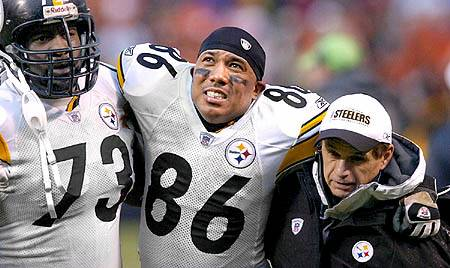

Dr. Maroon received an athletic scholarship to Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana where as an undergraduate, he was named a Scholastic All-American in football. Dr. Maroon has successfully maintained his personal athletic interests through participation in 9 marathons and more than 72 Olympic-distance triathlon events. However, his greatest athletic accomplishment is his participation in 8 Ironman triathlons (Hawaii – 1993, 2003, 2008, 2010, 2013; Canada – 1995; New Zealand – 1997; Germany – 2000), where he usually finishes in the top 10 of his age group. Recently, in July 2012 and 2013, he finished second and third, respectively, in his age group in the Muncie, Indiana half Ironman triathlon. In October 2013 he completed his 5th World Championship Ironman in Kona, Hawaii.

Dr. Maroon received an athletic scholarship to Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana where as an undergraduate, he was named a Scholastic All-American in football. Dr. Maroon has successfully maintained his personal athletic interests through participation in 9 marathons and more than 72 Olympic-distance triathlon events. However, his greatest athletic accomplishment is his participation in 8 Ironman triathlons (Hawaii – 1993, 2003, 2008, 2010, 2013; Canada – 1995; New Zealand – 1997; Germany – 2000), where he usually finishes in the top 10 of his age group. Recently, in July 2012 and 2013, he finished second and third, respectively, in his age group in the Muncie, Indiana half Ironman triathlon. In October 2013 he completed his 5th World Championship Ironman in Kona, Hawaii.